From Privilege to Purpose - A Journey into Rural India’s Everyday Struggles

November 08, 2024 by Maha Lakshme S

Disclaimer - The suggestions in this blog reflect solely my personal opinions. Avni, Samanvay, and Goonj do not engage in policy recommendations, and the views expressed here are not representative of these organizations.

Every field visit reminds me of how much privileged I am, and this one was no exception. Among Goonj's various initiatives, we witnessed one of their impactful community projects.

Goonj's Community-Driven Development Approach:

Goonj begins by identifying villages in need, often through local contacts. The villagers themselves decide on the development projects that would benefit their community most—whether it’s creating or rejuvenating ponds, lakes, and rivers, setting up kitchen gardens, laying roads, or other essential improvements. Goonj provides guidance to mobilise the villagers for these tasks using whatever tools they have, with a goal of instilling a sense of ownership. The hope is that communities will maintain these resources over time and, if needed, organise similar activities independently. Each family involved receives a cloth kit—80% clothing and 20% other essentials—as a token of appreciation rather than compensation, since the work is seen as a direct investment in their own wellbeing.

A significant focus of Goonj’s efforts is on providing clothing, a priority inspired by founder, Anshu Gupta’s early experiences in Delhi, where he witnessed the tragic effects of winter on those without warm clothing. This led him to start collecting clothes from urban areas, carefully processing and sorting them for distribution to people in need, and eventually founding Goonj.

To track field activities and kit distributions, Goonj uses the Avni platform. Field coordinators photograph the community activities and upload them to Avni for documentation and monitoring.

A Day in Torekolammanahall Village:

Wind turbines in Chitradurga

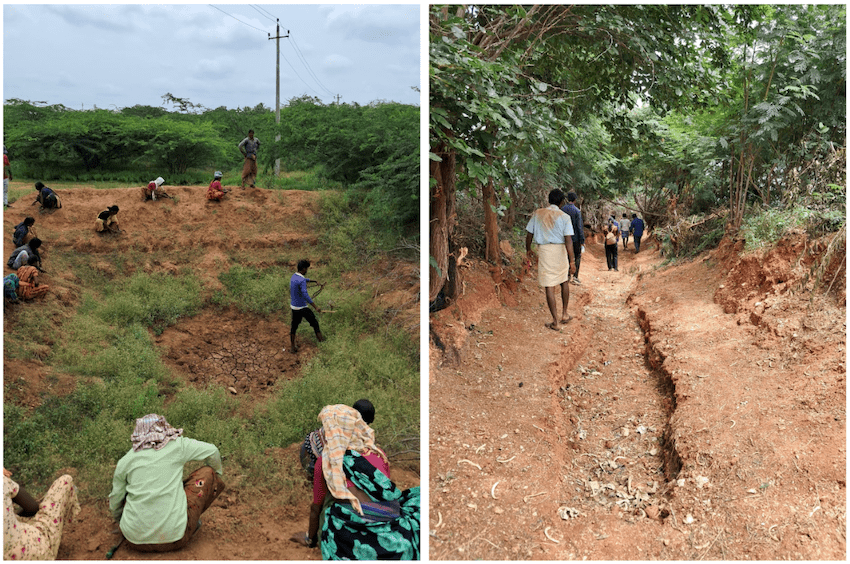

Torekolammanahall village is situated 50 kms from Chitradurga in Karnataka. We three from Samanvay foundation were accompanied by Vaishali from Goonj to the place where villagers were doing activities on ground. It was scorching hot when we got down that we regretted not bringing hats or sunscreen. We visited three ponds and a canal where villagers using shovel were rejuvenating it up for the below reasons:

- To recharge groundwater for irrigating nearby lands

- To keep the ponds free from algae

- To prevent snakes from inhabiting the area, and

- To avail water during the summer season

Community activities - (Left)Villagers rejuvenating their pond. (Right)Canal dug by villagers

The work in the Torekolammanahall was carried out by around 20 women, while their husbands travelled to nearby villages for work. Pause and give a thought—what are the hidden privileges we often take for granted?

Hidden Privilege: A Closer Look at Rural Inequities

Watching these women labour under the hot sun was a striking contrast to seeing the uploaded images of such activities from the comfort of our Bengaluru office. It was a reminder that, while we worry about hats or sunscreen, many people have needs far more fundamental than our conveniences, such as regular access to water. These villagers don’t have piped water to their homes, a reality that explains their reliance on ponds. At first glance, the above setup may seem similar to the goals of the MNREGA scheme. However, the above work was not done under it. The villagers told us that contractors often bring in machines to complete the work, claiming both the work and payment, leaving the villagers without the intended employment opportunities.

Stories from the Field: Voices of the Village Women

Vaishali and Himesh(from Samanvay) interacting with the villagers

After lunch, we had the chance to interact with a group of around 30 women from the village. Vaishali asked if the cloth kits and community projects had been beneficial, and they generally expressed satisfaction. Out of curiosity, we also asked about their general wellness. One old woman’s response stood out:

It would be helpful if you can provide us grains.

Read that again. Due to insufficient rainfall, crop yields from their small plots of land—one or two acres, in most cases—have been low. While they receive 5 kg of grain from the government as BPL families, it isn’t enough to last the month. Additionally, despite doing similar work, the women don’t receive equal pay to men.In talking with them, we realised that electricity is the only basic service they have consistently. Medical care is another issue. They have a 'doctor' in the neighbouring village, though he isn’t an MBBS or MD. He provides injections and a few medicines, though it’s uncertain what exactly is in those injections. A primary health centre is 8 km away, and a proper hospital is about 30 km from the village. The lack of an LPG connection for cooking only adds to their challenges. All this for a community of nearly 3,000 people within a 1 km radius.

Legal Rights and Rural Justice: A Reflection

Many questions arose within me during this visit. The Directive Principles of State Policy were designed as non-enforceable guidelines rather than rights, a decision made in our nascent independent India due to limited resources. However, it may be worth re-evaluating whether certain basic needs, like equal pay and access to legal aid, can transition into enforceable rights as we work toward a true welfare state.

Government partnerships with NGOs could be instrumental in this transformation. From what I gathered from Vaishali and other NGOs is that, the most effective outcomes emerge when district or state authorities engage wholeheartedly with NGOs. However, this level of partnership isn’t always achieved due to various challenges. Given the strengths each entity brings—NGOs with their capacity to innovate and governments with the resources to scale—it’s crucial for both to reflect on what holds these partnerships back and address these issues proactively.

Thanks to the insightful questions asked by my colleagues and Vaishali, I was able to add all the above discussed details. We returned feeling grateful and privileged, carrying both the memories of the visit and a handful of groundnuts freshly plucked from the fields.

Taqi from Samanvay, plucking groundnuts to take back to Samrasoi(Kitchen in Samanvay)

I know you are now curious to read my other blogs as well, so here you go :)

Tags